/ A place to find hope

Over 427,000 people live in Sokoto, a town in the northwest corner of Nigeria. It is home to a very special place, the Sokoto Noma Hospital. Founded in 1999, it is the only hospital in the country – and one of the few in the world.

Children recently diagnosed with noma get the antibiotics they need to stop the infection in Sokoto Noma Hospital.

The hospital is a haven for adults and children who have survived this painful disease and now need further treatment and reconstructive surgery. When new patients and their families walk through the blue and white hospital doors they find a safe place where they can meet other people with noma and they find a medical team ready to support them with free healthcare.

Since 2014, Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders (MSF) has been supporting the hospital with a programme of activities for people affected by noma, including noma survivors and their families.

The services, run in collaboration with the Nigerian Ministry of Health, focus on community outreach, active case finding in the region, health promotion, mental health support and reconstructive surgery by teams of Nigerian and international surgeons, anaesthesiologists and nurses, who travel to Sokoto four times a year.

The stages of treatment are challenging and patients stay in the hospital for long periods of time. Some children need to be treated for malnutrition and other diseases linked to the development of noma before surgery can begin.

There is a real sense of community in the hospital. The days in the ward pass slowly; patients cook and sing with the mental health team, mothers chat about their children’s conditions, and families help each other figure out how to keep some money coming in to support their family back home. After they are finally able to go home, patients come back regularly for follow-up visits and to undergo further operations. For these families, the journey they start in Sokoto is the most important of their lives.

/ OUTREACH ACTIVITIES

The importance of raising awareness

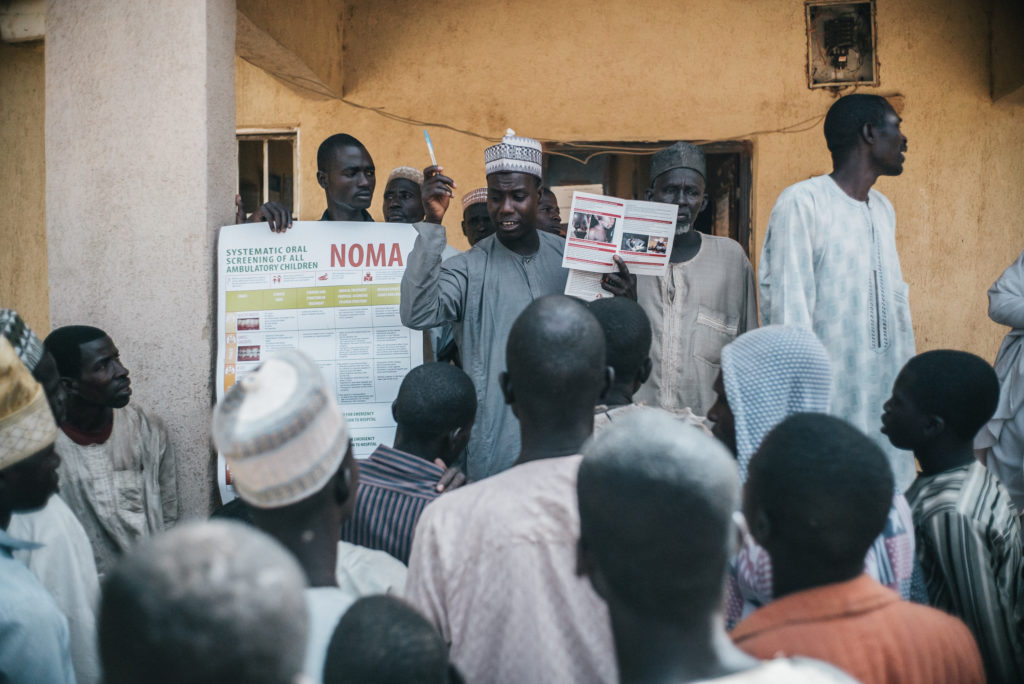

Prevention and awareness are two cornerstones of the fight against noma in northwest Nigeria. Most of the population, especially in the more remote villages, are not familiar with the disease and can’t identify it. An MSF outreach team, including a nurse and community health worker, visit villages in Sokoto, Kebbi and Zamfara states every day. They engage with local communities to explain what noma is and show them how to identify the symptoms.

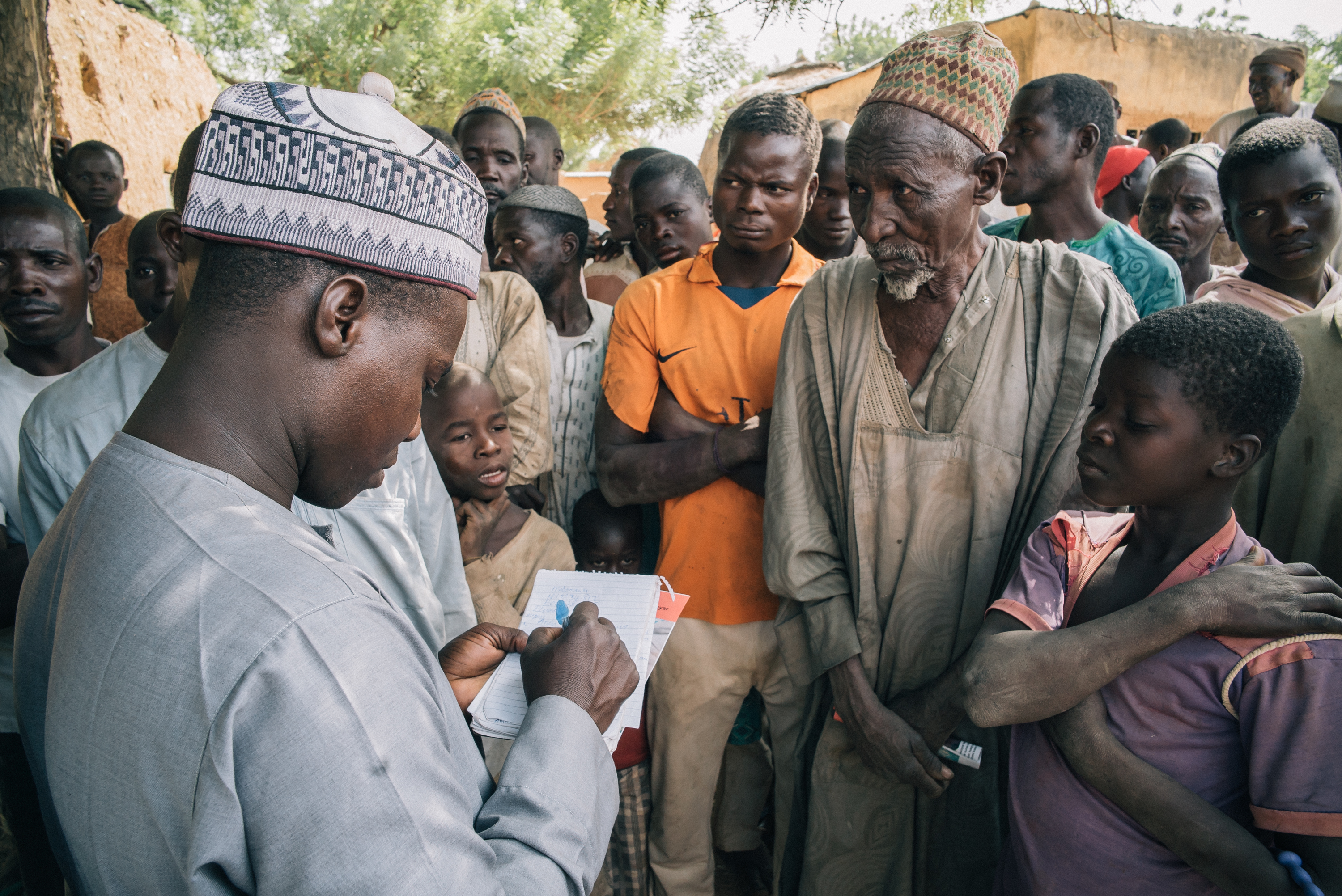

The outreach team finds noma survivors in remote and isolated villages. Some of them carry the scars of traditional healers’ treatments.

“The village head normally gathers members of the community, and we use posters to demonstrate the different stages of noma,” explains Nura Abubakar, MSF’s outreach supervisor. “Understanding the culture, religion and language of the region and collaborating with the elders is essential to our work.”

Nura’s team use posters, flyers and presentations to promote good dental hygiene and nutrition, two factors which reduce the risk of noma. They meet with patients that have not completed their treatment, check on survivors who have finished treatment and look for new patients.

Since he started working with MSF in the noma project in 2014, Nura has seen a significant improvement in community awareness about noma. “Before we started our outreach programme, people really didn’t know anything about noma. But now many can even identify the early signs, call us and help us find patients to bring them to the hospital.” Identifying patients early is important since active noma has a high rate of mortality, and it’s much easier and less costly to treat the disease in its early stages.

The outreach team travels every day to nearby villages with leaflets showing how to spot if someone has noma. They inform the population about the symptoms and causes of noma, promote good hygiene habits and explain the importance of early detection and treatment.

/ MENTAL HEALTH

Learning to leave the stigma behind

Teenagers are especially vulnerable to social stigma. In the hospital, the mental health team help them to overcome their fears.

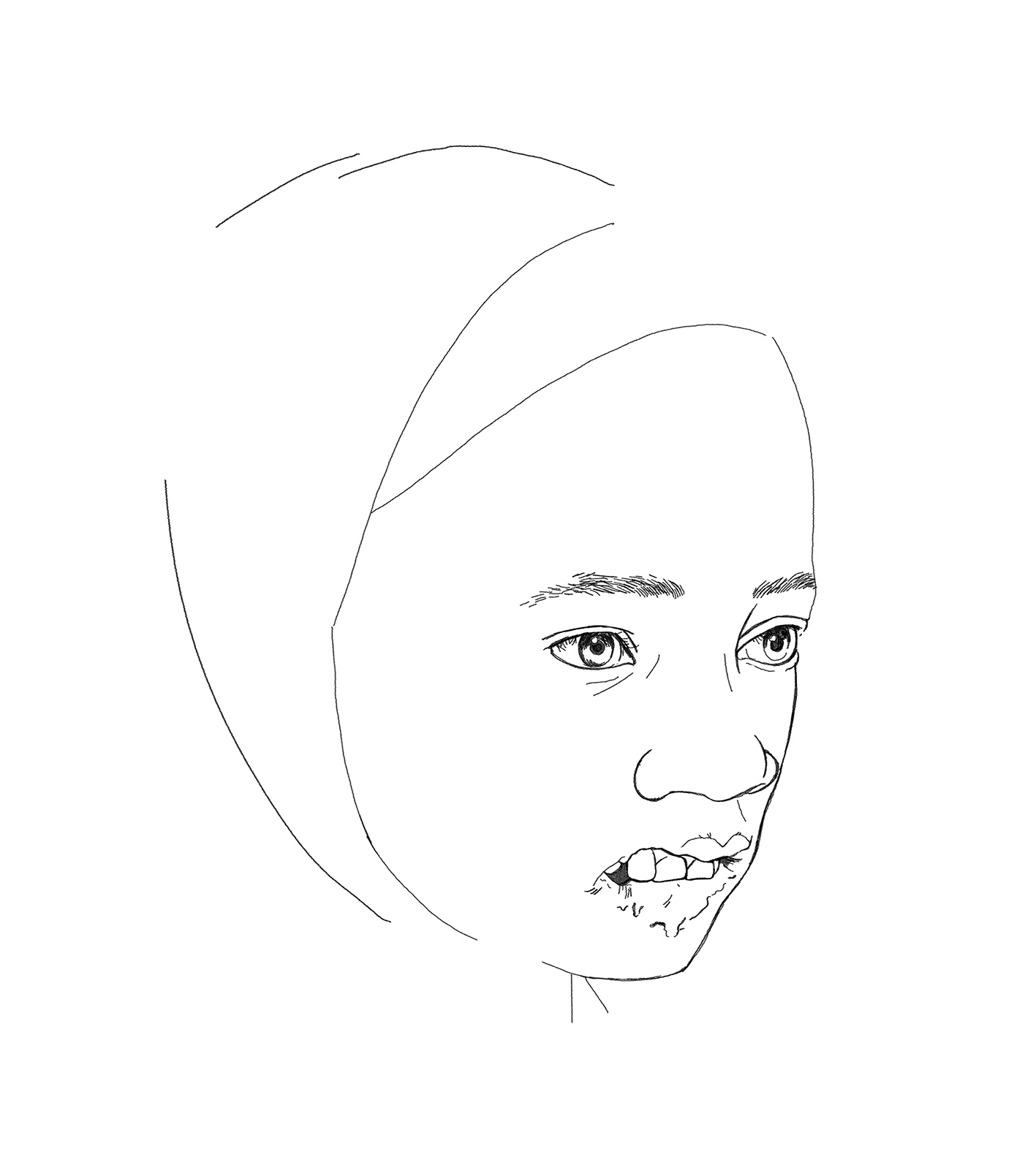

Because of their facial disfigurements, some patients isolate themselves from their communities to avoid being stigmatised. Their neighbours are sometimes afraid of contagion and repelled by their wounds which may include holes in the cheeks or loss of the jaw, nose or eye.

When patients arrive at the hospital, many cover their faces with scarves or try to avoid speaking to others. Some children have developmental problems due to being isolated within their homes.

But arriving at the hospital is also a positive experience for patients as it is often the first time they have met other people with noma. The mental health team is key in supporting patients to recover their self-esteem, express their feelings and overcome their fears.

Adebowale Murtala, Counsellor Educator

What were your first impressions of the hospital?

Adebowale Murtala, MSF counsellor educator.

Before I started working here in the hospital in 2016, I had seen pictures of noma survivors, but I could not really imagine what it would be like. On my first day, I remember introducing myself to patients, and I thought, ‘Who has done this to these children?’

I felt that somebody, somewhere, was not doing what they should to educate people about the dangers of noma. So, every time I have the opportunity, I explain to patients - or anybody who comes to the hospital - about the conditions that increase their chances of getting noma.

One of the main concerns that patients and caretakers have, is getting information about the disease. For many people, this is their first time seeing another person with noma. They are scared and often need somebody to encourage them. I tell them I have been here for 28 months and in that time no one has died here from noma. So they start to believe that they are going to get better. They start to trust us.

What is the most challenging thing for patients?

For a child the pain they feel makes them afraid. Adult patients can cope with the pain that comes with the reconstructive surgery, and they understand why it is necessary. They find the long stay in hospital the most difficult.

They have to leave their families and their commitments. Most of them are farmers and are worried that there will be no one at home to harvest or feed their animals.

They need somebody to encourage them. I tell them I have been here for 28 months and in that time no one has died here from noma.

How do the counsellors encourage adult patients and caretakers to stay at the hospital and finish treatment?

We visit the patients every day and get to know their personal stories, so for the people that have responsibilities at home we organise family support. We help them communicate with their relatives so they can check how things are going.

We also try to keep them busy. We have creative activities like toy-making sessions. They can then sell some of the toys they make and learn a new skill in the hospital that they can use back home.

What are the main activities your team runs at the hospital?

One of the most important activities is our daily stimulation sessions for young patients. We run these twice a day, right after they have their wound dressing. We do some exercises and play games with the children to help them cope with the pain.

The isolation and lack of socialisation caused by noma means that some children have under-developed or regressed cognitive abilities. Exercising their bodies relaxes their minds and we start to see smiles on their faces.

We also put on traditional calabash performances for patients once or twice a week. Calabash is a local drum that women play during ceremonies. It brings back a sense of normalcy to patients’ lives, as well as helping them remember tasks like hand hygiene and physical therapy.”

Stigma is clearly a problem for people who have survived noma. In what way are they stigmatised?

Stigmatisation in the community is a big problem for noma survivors. And it’s different for children and adults. A child will go to a local school or to the market and they will be bullied about their appearance, but it doesn’t change their habits so much.

For adults, this bullying causes low self-esteem and stops them from continuing their daily lives. When the adults come to the hospital, they are quieter than the children.

What is the most rewarding part of your job?

I feel fulfilled every time I see a patient come back for follow-up appointments. Can you imagine how it feels when a patient comes to you and they have not been able to open their mouth for 30 years? Or a baby comes in with extremely disfiguring injuries? But after a while, they can smile and eat again. So the most rewarding part for me is to see how all of the efforts from the different teams − including the work of the caretakers − put a smile back on their faces.

Is there a patient that particularly stands out in your memory?

There was a six-year-old girl who came to the hospital with her grandmother. During one of our sessions, I asked the grandmother if she would stay until the girl got better, and she said, ‘Of course, I will stay.’

She told me the parents left the girl at her house when she got noma and that every day she would remove maggots from the girl’s face and kill them, and cry. She said, ‘If I did not leave her then, would I leave her now?’ The girl is much better now. She still has one surgery to go, and I really hope to see them both coming back to the hospital for the next intervention.

So, every time I have the opportunity, I explain to patients - or anybody who comes to the hospital - about the conditions that increase their chances of getting noma.

/ RECONSTRUCTIVE SURGERY

Dreaming of a new face

Four times a year, a team of highly trained plastic and maxillofacial surgeons, anaesthesiologists and nurses from all over the world arrive at Sokoto Noma Hospital, in Nigeria. They have one clear objective: to perform life-changing reconstructive surgery for noma survivors.

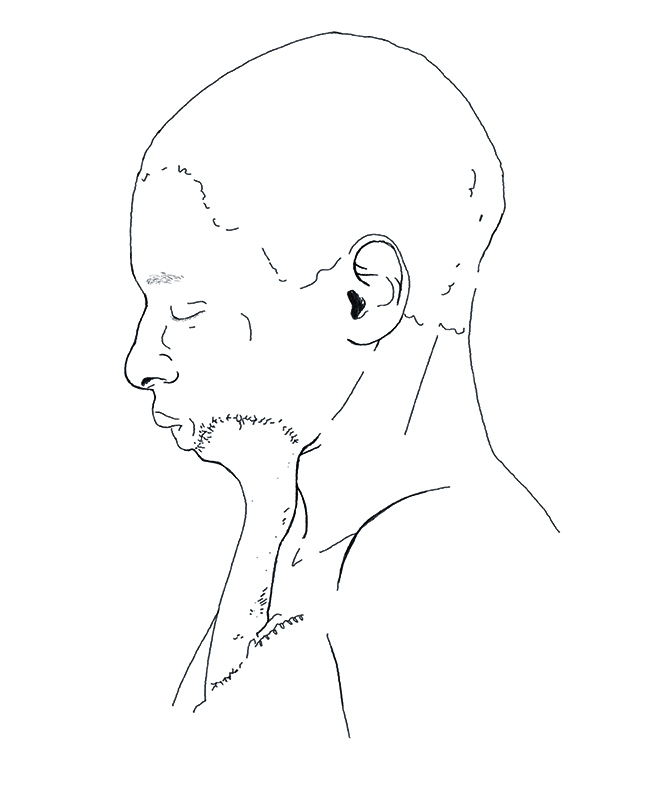

‘The flap’ is a reliable surgery method that is based on creating a flap with the patient’s own skin, using normal tissues from another area to reconstruct the area destroyed by the disease. In a second surgery, the flap is divided from its base to continue the reconstruction.

Most of the patients have been waiting months for surgery. They welcome the medical team with a mix of happiness, nervousness and fear. No one wants to leave the hospital again without going through surgery. They hope it will help them get their normal lives back.

The surgeons and anaesthetists check the patient’s wounds and medical condition to evaluate whether they can operate now or whether the patient should for the next surgical team in three months' time.

Once the surgery starts, the excitement in the hospital is palpable. The day patients have waited so long for is finally here. Even though their recovery will take a long time, the prospect of going home finally feels real and this is a good reason to be happy.

Inside the operating theatre, the team spends several hours operating on the more complicated cases. A patient with a trismus, a fusion of the jaw caused by noma which prevents it from opening, can require several hours of surgery and a long recovery in the post-operative ward.

'Intervention time' in Sokoto Noma Hospital means worried parents waiting to see their child coming out of surgery. A hospital full of activity as a team of surgeons do their best to achieve the results long-awaited by their patients: a new opportunity to resume their lives.

Footnotes: Drawings & infographics by Chloé Fournier / Pictures & Videos by Claire Jeantet & Fabrice Caterini © Inediz - All rights reserved